Arthur Homer Wainer1

M, b. 13 November 1875, d. August 1962

Arthur Homer Wainer married Eleanor Cornwall.1 Arthur Homer Wainer was born on 13 November 1875 in Mount Tabor, Monroe County, Indiana.1 He was pipefitter for railroad shops in 1930.1 He and Eleanor Cornwall lived in 1930 in Elkins, Randolph County, West Virginia.1 Arthur Homer Wainer died in August 1962 in West Virginia at age 86.

Child of Arthur Homer Wainer and Eleanor Cornwall

- Stephen Homer Wainer+1 b. 16 Aug 1908, d. 2 Jun 1956

Citations

- [S207] United States Federal Census, Washington, District of Columbia, Population Schedule: Elkins, Randolph, West Virginia, Emuneration District: 42-14, Supervisor District: 8, Sheet: 9B, Dwelling: 40, Family Number: 41, Date: 1930.

Eleanor Cornwall

F, b. 1875

Eleanor Cornwall married Arthur Homer Wainer.1 Her married name was Wainer. Eleanor Cornwall was born in 1875 in Oakland, Garrett County, Maryland. She and Arthur Homer Wainer lived in 1930 in Elkins, Randolph County, West Virginia.1

Child of Eleanor Cornwall and Arthur Homer Wainer

- Stephen Homer Wainer+ b. 16 Aug 1908, d. 2 Jun 1956

Citations

- [S207] United States Federal Census, Washington, District of Columbia, Population Schedule: Elkins, Randolph, West Virginia, Emuneration District: 42-14, Supervisor District: 8, Sheet: 9B, Dwelling: 40, Family Number: 41, Date: 1930.

Mary Helen Wooddell

F

Mary Helen Wooddell married Stephen Homer Wainer, son of Arthur Homer Wainer and Eleanor Cornwall, on 13 March 1934 at Mineral, West Virginia.

Children of Mary Helen Wooddell and Stephen Homer Wainer

- Stephen Wainer

- Thomas Leigh Wainer b. 10 Dec 1933, d. 22 Dec 1958

- Kathryn "Kitty" Wainer b. 3 Oct 1935, d. 16 Jul 2001

Kathryn "Kitty" Wainer

F, b. 3 October 1935, d. 16 July 2001

Her married name was King. Kathryn "Kitty" Wainer married Robert King. Kathryn "Kitty" Wainer was born on 3 October 1935 in Elkins, Randolph County, West Virginia. She was the daughter of Stephen Homer Wainer and Mary Helen Wooddell. Kathryn "Kitty" Wainer died on 16 July 2001 in Las Vegas, Nevada, at age 65.

Thomas Leigh Wainer

M, b. 10 December 1933, d. 22 December 1958

Thomas Leigh Wainer was born on 10 December 1933 in Oakland, Maryland. He was the son of Stephen Homer Wainer and Mary Helen Wooddell. Thomas Leigh Wainer died on 22 December 1958 in Lewiston, Idaho, at age 25 of cerebal concussion due to gunshot wound.

Robert King

M

Robert King married Kathryn "Kitty" Wainer, daughter of Stephen Homer Wainer and Mary Helen Wooddell.

Amie Louise Hall1,2

F

Amie Louise Hall married Maurice Myron Manown, son of James Franklin Manown and Myrtle S. (Mirtie Belle) Rector, circa 1927.1

Child of Amie Louise Hall and Maurice Myron Manown

- Maurice Myron Manown Jr.+1 b. 24 Jul 1928, d. 11 Jan 1999

Citations

- [S208] United States Federal Census, Washington, District of Columbia, Population Schedule: Fairmont, Marion, West Virginia, Emuneration District: 25-13, Supervisor District: 2, Sheet: 11B, Dwelling: 263, Family Number: 280, Date: 1930.

- [S445] Email from Layla Rudy dated 9/28/2008 to Hunter Wayne Bagwell; Subject Line: Re: Maurice Myron Manown.

Maurice Myron Manown Jr.1,2

M, b. 24 July 1928, d. 11 January 1999

Maurice Myron Manown Jr. was born on 24 July 1928 in West Virginia.1 He was the son of Maurice Myron Manown and Amie Louise Hall.1 Enlisted in the US Army (SP3) in both World War II and Korea. Maurice Myron Manown Jr. married Lucy Angelita Archuleta in 1950 at Alburquerque, New Mexico.2 Maurice Myron Manown Jr. lived on 10 January 1999 in Alameda, Alameda County, California. He died on 11 January 1999 in Oakland, Alameda County, California, at age 70 Obituary was in the Oakland Tribune; 1999-1-13. He was buried on 15 January 1999 at Santa Fe National Cemetery, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Section 10 Site 999.

Children of Maurice Myron Manown Jr. and Lucy Angelita Archuleta

Citations

- [S208] United States Federal Census, Washington, District of Columbia, Population Schedule: Fairmont, Marion, West Virginia, Emuneration District: 25-13, Supervisor District: 2, Sheet: 11B, Dwelling: 263, Family Number: 280, Date: 1930.

- [S445] Email from Layla Rudy dated 9/28/2008 to Hunter Wayne Bagwell; Subject Line: Re: Maurice Myron Manown.

Lucy O. Cogburn

F, b. circa 1852, d. 9 March 1880

Lucy O. Cogburn was born circa 1852 in Georgia. She was the daughter of James Floyd Cogburn and Elizabeth Eveline Fields. Lucy O. Cogburn died on 9 March 1880.

John T. Cogburn

M, b. 4 May 1856, d. before 5 March 1894

John T. Cogburn was born on 4 May 1856 in Cherokee County, Georgia. He was the son of James Floyd Cogburn and Elizabeth Eveline Fields. John T. Cogburn died before 5 March 1894 in Texas.

Joseph H. Cogburn

M, b. 13 September 1867, d. 22 August 1930

Joseph H. Cogburn was born on 13 September 1867 in Milton County, Georgia. He was the son of James Floyd Cogburn and Elizabeth Eveline Fields. Joseph H. Cogburn died on 22 August 1930 in Marietta, Cobb County, Georgia, at age 62.

Carolyn Sue Cary1

F

Carolyn Sue Cary is the daughter of William Watson Cary Jr. and Agnes Sue Allen. Carolyn Sue Cary married (?) Morris.1

Citations

- [S728] Email from Mik dated February 2009 to Hunter Wayne Bagwell - Subject Line: Agnes Sue Allen Family History.

Elizabeth Allen Cary1

F

Elizabeth Allen Cary is the daughter of William Watson Cary Jr. and Agnes Sue Allen.1 Elizabeth Allen Cary married (?) Cloys.1

Citations

- [S728] Email from Mik dated February 2009 to Hunter Wayne Bagwell - Subject Line: Agnes Sue Allen Family History.

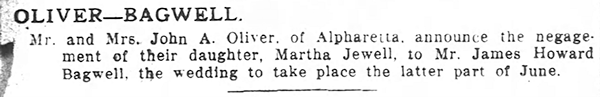

Martha Jewel Oliver

F, b. 1899, d. 1972

James Howard Bagwell and Martha Oliver - Marriage Annoucement

The Atlanta Constitution, May 2, 1920 - Page 02

The Atlanta Constitution, May 2, 1920 - Page 02

Children of Martha Jewel Oliver and James Howard Bagwell

- Infant Son Bagwell b. 3 May 1921, d. 3 May 1921

- Jewel Virginia Bagwell1 b. 25 Jun 1923, d. 4 Jun 2019

Citations

- [S215] United States Federal Census, Washington, District of Columbia, Population Schedule: Militia District 792, Cherokee County, Georgia, Emuneration District: 29-1, Supervisor District: 2, Sheet: 21B, Dwelling: 383, Family Number: 484, Date: 1930.

- [S5517] Martha Jewell Oliver Bagwell Grave Stone, Find a Grave, www.findagrave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/150974082

Jewel Virginia Bagwell1

F, b. 25 June 1923, d. 4 June 2019

Jewel Virginia Bagwell was born on 25 June 1923 in Georgia.1,2 She was the daughter of James Howard Bagwell and Martha Jewel Oliver.1 As of 2 May 1947,her married name was Spears. Jewel Virginia Bagwell married Leland Ernest Spears on 2 May 1947. Jewel Virginia Bagwell died on 4 June 2019 in Canton, Cherokee County, Georgia, at age 95

Virginia Bagwell Spears, age 95, of Canton, Georgia passed away June 4, 2019 with family by her side at Cameron Hall.

She was born to Howard and Jewel Bagwell on June 25, 1923.

She was married to the late Lee Spears, Jr. in 1947.

Mrs. Spears is survived by her three children; James Spears (Helen) of Ball Ground, GA, Virginia Schmeelk (Reed) of Cumming, GA , Tricia Bridges (Don) of Washington, GA, five grandchildren; Laura Spears Coogle (Trey), Atlanta, GA, Grant Schmeelk (Sarah), Cumming, GA, Derek Schmeelk (Jodi), Mt. Pleaseant, SC, Kristin Bridges Stevens (Greg), Maggie Valley, NC, Marc Bridges (Andrea), Washington, GA. She is also survived by ten great-grandchildren.

Virginia was preceded in death by her husband, Lee Spears, Jr. and her two beloved grandchildren, Joshua Spears and Brittany Schmeelk.

Virginia graduated from Canton High School and received a Bachelor’s Degree from the University of Alabama. She was a true southern lady who loved to entertain and give back to her community. She worked for many years as a volunteer with the American Cancer Society and was the first president of the Trayleah Garden Club. Virginia was one of the founding members of the Canton Service League. She taught at Cherokee High School and was Director of the Canton Housing Authority for a number of years.

Virginia was loved by her family and friends and will be missed by many.

The family will receive visitors at Darby Funeral Home in Canton, GA on Thursday, June 6th from 5-8pm and Friday, June 7th from 10-11.

A funeral service will be held Friday, June 7th at 11am in the Chapel at Darby Funeral Home. Interment will follow at Cherokee Memorial Park.

In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made to the Alzheimers Association.2

She was buried at Cherokee Memorial Park, Canton, Cherokee County, Georgia.2

Virginia Bagwell Spears, age 95, of Canton, Georgia passed away June 4, 2019 with family by her side at Cameron Hall.

She was born to Howard and Jewel Bagwell on June 25, 1923.

She was married to the late Lee Spears, Jr. in 1947.

Mrs. Spears is survived by her three children; James Spears (Helen) of Ball Ground, GA, Virginia Schmeelk (Reed) of Cumming, GA , Tricia Bridges (Don) of Washington, GA, five grandchildren; Laura Spears Coogle (Trey), Atlanta, GA, Grant Schmeelk (Sarah), Cumming, GA, Derek Schmeelk (Jodi), Mt. Pleaseant, SC, Kristin Bridges Stevens (Greg), Maggie Valley, NC, Marc Bridges (Andrea), Washington, GA. She is also survived by ten great-grandchildren.

Virginia was preceded in death by her husband, Lee Spears, Jr. and her two beloved grandchildren, Joshua Spears and Brittany Schmeelk.

Virginia graduated from Canton High School and received a Bachelor’s Degree from the University of Alabama. She was a true southern lady who loved to entertain and give back to her community. She worked for many years as a volunteer with the American Cancer Society and was the first president of the Trayleah Garden Club. Virginia was one of the founding members of the Canton Service League. She taught at Cherokee High School and was Director of the Canton Housing Authority for a number of years.

Virginia was loved by her family and friends and will be missed by many.

The family will receive visitors at Darby Funeral Home in Canton, GA on Thursday, June 6th from 5-8pm and Friday, June 7th from 10-11.

A funeral service will be held Friday, June 7th at 11am in the Chapel at Darby Funeral Home. Interment will follow at Cherokee Memorial Park.

In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made to the Alzheimers Association.2

She was buried at Cherokee Memorial Park, Canton, Cherokee County, Georgia.2

Citations

- [S215] United States Federal Census, Washington, District of Columbia, Population Schedule: Militia District 792, Cherokee County, Georgia, Emuneration District: 29-1, Supervisor District: 2, Sheet: 21B, Dwelling: 383, Family Number: 484, Date: 1930.

- [S5518] Virginia Bagwell Spears Grave Stone, Find a Grave, www.findagrave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/199799402

Larkin M. Bagwell1,2

M, b. 9 September 1841, d. 29 January 1905

Larkin M. Bagwell was also known as Larkin R.M.V. Bagwell. He was born on 9 September 1841 in Gwinnett County, Georgia.2,1,3 He was the son of Redmond Reed Bagwell and Rhoda Corley.2 Enlisted as a private in the Company G, 15th Infantry Regiment Alabama of the Confederate States of America (CSA).

The 15th Regiment of Alabama Infantry was a Confederate volunteer infantry unit from the state of Alabama during the American Civil War. Recruited from six counties in the southeastern part of the state, it fought mostly with Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, though it also saw brief service with Braxton Bragg and the Army of Tennessee in late 1863 before returning to Virginia in early 1864 for the duration of the war. Out of 1958 men listed on the regimental rolls throughout the conflict, 261 are known to have fallen in battle, with sources listing an additional 416 deaths due to disease. 218 were captured (46 died), 66 deserted and 61 were transferred or discharged. By the end of the war, only 170 men remained to be paroled.

The 15th Alabama is most famous for being the regiment that confronted the 20th Maine on Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. Despite several ferocious assaults, the 15th Alabama was ultimately unable to dislodge the Union troops, and was eventually forced to retreat in the face of a desperate bayonet charge led by the 20th Maine's commander, Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain. This assault was recreated in Ronald F. Maxwell's 1993 film Gettysburg.

The 15th Alabama was organized by James Cantey, a planter originally from South Carolina, who was residing in Russell County, Alabama, at the outset of the Civil War. "Cantey's Rifles" formed at Ft. Mitchell, on the Chattahoochee River, in May 1861. Cantey's company was joined by ten other militia companies, all of which were sworn into state service by governor Andrew B. Moore on July 3, 1861, with Cantey as Regimental Commander.

One of these companies, from Henry County, was formed by William C. Oates, a lawyer and newspaperman from Abbeville. Oates, who would later command the whole regiment at Little Round Top, put together a company composed mostly of Irishmen recruited from the area, calling them "Henry Pioneers" or "Henry County Pioneers". Other observers, after seeing their colorful uniforms (bright red shirts, with Richmond grey frock coats and trousers), dubbed them "Oates' Zouaves".

According to one source, the youngest private in the 15th Alabama was only thirteen years old; the oldest, Edmond Shepherd, was seventy.

The 15th initially consisted of approximately 900 men; its companies, and their counties of origin, were:

Co. "A", known as "Cantey's Rifles", from Russell County;

Co. "B", known as the "Midway Southern Guards", from Barbour County;

Co. "C", no nickname given, from Macon County;

Co. "D", known as the "Fort Browder Roughs", from Barbour County;

Co. "E", known as the "Beauregards", from Dale County (which then included parts of present-day Geneva and Houston counties);

Co. "F", known as the "Brundidge Guards", from Pike County;

Co. "G", known as the "Henry Pioneers", from Henry County (which then included nearly all of present-day Houston County);

Co. "H", known as the "Glenville Guards", from Barbour and Dale counties;

Co. "I", no nickname given, from Pike County;

Co. "K", known as the "Eufaula City Guard", from Barbour County; and

Co. "L", no nickname given, from Pike County.

Following its formal swearing-in, the 15th Alabama was ordered to Pageland Field, Virginia, for training and drill. During their sojourn at Pageland, the regiment lost 150 men to measles. In September 1861, the 15th was transferred to Camp Toombes, Virginia, in part to escape the measles outbreak.

Companies "A" and "B" of the 15th Alabama were equipped with the M1841 Mississippi Rifle, a .54 caliber percussion rifle that had seen extensive service in the Mexican-American War and was highly regarded for its accuracy and ease of use. The other companies in the regiment were given older "George Law" smoothbore muskets, which had been converted from flintlocks to percussion rifles. Later, the regiment received British Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-muskets and Springfield Model 1861 rifled muskets. Since the 15th had initially enlisted for three years, it received its arms from the Confederate government, which refused to provide weapons to any regiment enlisting for a lesser period.

While details of the specific uniforms worn by other companies of the 15th has not been preserved, Oates' Co. "G" is recorded to have sported, in addition to their red and gray clothing, a "colorful and diverse attire of headgear". Each cap bore an "HP" insignia, which stood for "Henry Pioneers" (though some said it actually meant "Hell's Pelters"). Each soldier also wore a "secession badge", with the motto: "Liberty, Equality and Fraternity", which had been the motto of the French Revolution.

At Camp Toombs, the 15th Alabama was brigaded with the 21st Georgia Volunteer Infantry, the 21st North Carolina Infantry and the 16th Mississippi Infantry regiments in Trimble's Brigade of Ewell's Division, part of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. After that force moved over toward Yorktown, the 15th was transferred to Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson's division, where it participated in his Valley Campaign. During this time, the 15th participated in the following engagements:

Battle of Front Royal on May 23, 1862; negligible losses.

First Battle of Winchester on May 25, 1862; negligible losses.

Battle of Cross Keys on June 8, 1862; 9 killed and 33 wounded, out of 426 engaged.

Following the Battle of Cross Keys, the 15th was mentioned in dispatches by its division commander, Maj. Gen. Ewell, who stated that "the regiment made a gallant resistance, enabling me to take position at leisure". Its brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Trimble, also singled out the regiment for honors during this engagement: "to Colonel Cantey for his skillful retreat from picket, and prompt flank maneuver, I think special praise is due". During this particular engagement, soldiers of the 15th Alabama had the unusual opportunity of participating in every major phase of a single battle, starting with the opening skirmish at Union Church on the forward left flank, followed by withdrawing beneath the artillery duel in the center, and then finally participating in Trimble's ambush of the 8th New York and subsequent counterattack on the Confederate right flank, which brought the battle to its conclusion.

Seven Days Battles

Following the victorious conclusion of Jackson's Valley Campaign, the 15th participated in Jackson's attack on Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's flank during the Seven Days Battles. During this time, the 15th fought in the following sorties:

Second Battle of Manassas battlefield

Battle of Gaines' Mill on June 27-28, 1862; 34 killed and 110 wounded, out of 412 engaged.

Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862; negligible losses.

Northern Virginia Campaign

Following McClellan's retreat from Richmond, the 15th was engaged in the Northern Virginia Campaign, where it participated in the following battles:

Battle of Warrenton Springs Ford on August 12, 1862; losses not given.

Battle of Hazel River, Virginia, on August 22, 1862; losses not given.

Battle of Kettle Run (called "Manassas Junction" in regimental records) on August 30, 1862; 6 killed and 22 wounded.

Second Battle of Manassas, on August 30, 1862; 21 killed and 91 wounded, out of 440 engaged.

Battle of Chantilly, on September 1, 1862; 4 killed and 14 wounded.

Battle of Antietam by Kurz and Allison

Maryland Campaign

Next up was Lee's Maryland Campaign, where the 15th Alabama saw action at:

Battle of Harper's Ferry from September 12-15, 1862; negligible losses.

Battle of Antietam (called "Sharpsburg" in regimental records) on September 17, 1862; 9 killed and 75 wounded, out of 300 engaged.

Battle of Shepherdstown on September 19, 1862; losses not given.

After Antietam, acting brigade commander Col. James A. Walker cited Cpt. Isaac B. Feagin, acting regimental commander, for outstanding performance while extolling the regiment as a whole: "Captain Feagin, commanding the Fifteenth Alabama regiment, behaved with a gallantry consistent with his high reputation for courage and that of the regiment he commanded".

Fredericksburg and Suffolk; reassignment

Following the Confederate defeat at Antietam, the 15th Alabama participated with Jackson's corps at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 15, 1862. Total casualties there were 1 killed and 34 wounded. The regiment was then reassigned in May 1863 to General James Longstreet's corps, which was then participating in the Siege of Suffolk, Virginia. Here it formed part of the newly created "Alabama Brigade" under Evander Law in General Hood's division, The 15th and lost 4 killed and 18 wounded at Suffolk.

The Great Snowball Fight

On January 29, 1863, the 15th Alabama participated with several other regiments of the Army of Northern Virginia in what became known as "The Great Snowball Fight of 1863". Over 9000 Confederate soldiers engaged in a spontaneous, day-long free-for-all using snowballs and rocks, in which only two soldiers were seriously injured (neither from the 15th).

Oates takes command

Along with its change in Divisional assignment, the 15th Alabama received a new regimental commander: Lt. Col. William C. Oates, who had originally organized Co. "G" when the regiment first formed in 1861. Oates had lived a drifter's existence in Texas during his early adulthood, participating in numerous street brawls and spending time as a gambler. However, by 1861 he had returned to Alabama, finished his schooling, studied law, and set up a successful practice in Henry County that also included ownership of a weekly newspaper in his hometown. Opposed to Abraham Lincoln's election, Oates cautioned against precipitate secession; however, once Alabama decided to leave the Union, he threw himself wholeheartedly into the Southern cause, raising a company of volunteers that became Co. "G" of the 15th Alabama. After Cantey's promotion and transfer to a new position, Oates assumed command of the regiment as a whole. In later years, Oates would serve as Governor of Alabama, and would also command three U.S. Brigades (none of which saw combat) during the Spanish-American War.

While some of his men thought Oates to be too aggressive for his own good and theirs, most admired his courage and affirmed that he was always to be found at the front of his men, in the thick of combat, and that he never asked them to go anywhere that he was not willing to go himself. A political rival, Alexander Lowther, would replace Oates as regimental commander in July 1864 after allegedly engineering Oates' removal from command. It was Oates, however, who led the 15th Alabama into its most noted engagement of the war, at Little Round Top on July 2, 1863, during the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Action at Gettysburg

Main articles: Battle of Gettysburg, Second Day and Little Round Top

Little Round Top

During the Battle of Gettysburg, the 15th Alabama and the rest of Law's Brigade formed part of Maj. Gen. John B. Hood's division, which was a part of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's corps. Arriving on the field late in the evening on July 1, the 15th played no appreciable role in the contest's first day. This changed on the 2nd, as Gen. Robert E. Lee had ordered Longstreet to launch a surprise attack with two of his divisions against the Federal left flank and their positions atop Cemetery Hill. During the course of this engagement, which was launched late in the afternoon of July 2, the 15th Alabama found itself advancing over rough terrain on the eastern side of the Emmitsburg Road, which combined with fire from the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters at nearby Slyder's Farm to compel Law's brigade (including the 15th Alabama) to detour around the Devil's Den and over the Big Round Top toward Little Round Top. During this time, the 15th was under constant fire from Federal sharpshooters, and the regiment became temporarily separated from the rest of the Alabama brigade as it made its way over Big Round Top.

Little Round Top, which dominated the Union position on Cemetery Ridge, was initially unoccupied by Union troops. Union commander Maj. Gen. George Meade's chief engineer, Brig. Gen Gouverneur K. Warren, had climbed the hill on his superior's orders to assess the situation there; he noticed the glint of Confederate bayonets to the hill's southwest, and realized that a Southern attack was imminent. Warren's frantic cry for reinforcements to occupy the hill was answered by Col. Strong Vincent, commanding the Third Brigade of the First Division of the Union V Corps. Vincent rapidly moved the four regiments of his brigade onto the hill, only ten minutes ahead of the approaching Confederates. Under heavy fire from Southern batteries, Vincent arranged his four regiments atop the hill with the 16th Michigan to the northwest, then proceeding counterclockwise with the 44th New York, the 83rd Pennsylvania, and finally, at the end of the line on the southern slope, the 20th Maine. With only minutes to spare, Vincent told his regiments to take cover and await the inevitable Confederate assault; he specifically ordered Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain, commanding the 20th Maine (at the extreme end of the Union line), to hold his position to the last man, at all costs. Were Chamberlain's regiment to be forced to retreat, the other regiments on the hill would be compelled to follow suit, and the entire left flank of Meade's army would be in serious jeopardy, possibly leading them to retreat and giving the Confederates their desperately needed victory at Gettysburg.

The 15th Alabama attacks

In their attack on Little Round Top, the 15th Alabama would be joined by the 4th and 47th Alabama Infantry, and also by the 4th and 5th Texas Infantry regiments. All of these units were thoroughly exhausted at the time of the assault, having marched in the July heat for over 20 miles (37 kilometers) prior to the actual attack. Furthermore, the canteens of the Southerners were empty, and Law's command to advance did not give them time to refill them. Approaching the Union line on the crest of the hill, Law's men were thrown back by the first Union volley and withdrew briefly to regroup. The 15th Alabama repositioned itself further to the right, attempting to find the Union left flank which, unbeknownst to it, was held by Chamberlain's 20th Maine.

Chamberlain, meanwhile, had detached Company "B" of his regiment and elements of the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters, ordering them to take a concealed position behind a stone wall 150 yards to his east, hoping to guard against a Confederate envelopment.

Seeing the 15th Alabama shifting around his flank, Chamberlain ordered the remainder of his 385 men to form a single-file line. The 15th Alabama charged the Maine troops, only to be repulsed by furious rifle fire. Chamberlain next ordered the southernmost half of his line to "refuse the line", meaning that they formed a new line at an angle to the original force, to meet the 15th Alabama's flanking maneuver. Though it endured incredible losses, the 20th Maine managed to hold through five more charges by the 15th over a ninety-minute period. Col. Oates, commanding the regiment, described the action in his memoirs, forty years later:

"Vincent's brigade, consisting of the Sixteenth Michigan on the right, Forty-fourth New York, Eighty-third Pennsylvania, and Twentieth Maine regiments, reached this position ten minutes before my arrival, and they piled a few rocks from boulder to boulder, making the zigzag line more complete, and were concealed behind it ready to receive us. From behind this ledge, unexpectedly to us, because concealed, they poured into us the most destructive fire I ever saw. Our line halted, but did not break. The enemy was formed in line as named from their right to left. ... As men fell their comrades closed the gap, returning the fire most spiritedly. I could see through the smoke men of the Twentieth Maine in front of my right wing running from tree to tree back westward toward the main body, and I advanced my right, swinging it around, overlapping and turning their left. I ordered my regiment to change direction to the left, swing around, and drive the Federals from the ledge of rocks, for the purpose of enfilading their line ... gain the enemy's rear, and drive him from the hill. My men obeyed and advanced about half way to the enemy's position, but the fire was so destructive that my line wavered like a man trying to walk against a strong wind, and then slowly, doggedly, gave back a little; then with no one upon the left or right of me, my regiment exposed, while the enemy was still under cover, to stand there and die was sheer folly; either to retreat or advance became a necessity. ... Captain [Henry C.] Brainard, one of the bravest and best officers in the regiment, in leading his company forward, fell, exclaiming, 'O God! that I could see my mother,' and instantly expired. Lieutenant John A. Oates, my dear brother, succeeded to the command of the company, but was pierced through by a number of bullets, and fell mortally wounded. Lieutenant [Barnett H.] Cody fell mortally wounded, Captain [William C.] Bethune and several other officers were seriously wounded, while the carnage in the ranks was appalling. I again ordered the advance, knowing the officers and men of that gallant old regiment, I felt sure that they would follow their commanding officer anywhere in the line of duty. I passed through the line waving my sword, shouting, 'Forward, men, to the ledge!' and promptly followed by the command in splendid style. We drove the Federals from their strong defensive position; five times they rallied and charged us, twice coming so near that some of my men had to use the bayonet, but in vain was their effort. It was our time now to deal death and destruction to a gallant foe, and the account was speedily settled. I led this charge and sprang upon the ledge of rock, using my pistol within musket length, when the rush of my men drove the Maine men from the ledge. ... About forty steps up the slope there is a large boulder about midway the Spur. The Maine regiment charged my line, coming right up in a hand-to-hand encounter. My regimental colors were just a step or two to the right of that boulder, and I was within ten feet. A Maine man reached to grasp the staff of the colors when Ensign [John G.] Archibald stepped back and Sergeant Pat O'Connor stove his bayonet through the head of the Yankee, who fell dead."

Battle of Little Round Top, final assault, showing the 15th Alabama's assault against the 20th Maine

Chamberlain's desperate charge

Out of ammunition, and facing what he was sure would be yet another determined assault by the Alabamians, Col. Chamberlain decided upon a most unorthodox response: ordering his men to fix bayonets, he led what was left of his outfit in a pell-mell charge down the hill, executing a combined frontal assault and flanking maneuver that caught the 15th Alabama completely by surprise. Unbeknownst to Chamberlain, Oates had already decided to retreat, realizing that his ammunition was running low, and worried about a possible Union attack on his own flank or rear. His younger brother lay dying on the field, and the blood from his regiment's dead and wounded "was standing in puddles on some of the rocks". Hardly had Oates ordered the withdrawal than Chamberlain began his charge, which combined with fire from "B" company and the hidden sharpshooters to cause the 15th to rush madly down the hill to escape. Oates later admitted that "we ran like a herd of wild cattle" during the retreat, which took those surviving members of the 15th (including Oates) who weren't captured by Chamberlain's men up the slopes of Big Round Top and toward Confederate lines.

In later years, Oates would assert that the 15th Alabama's assault had failed because no other Confederate regiment appeared in support of his unit during the attack. He insisted that if but one other regiment had joined his attack on the far left of the Union army, they would have swept the 20th Maine from the hill and turned the Union flank, "which would have forced Meade's whole left wing to retire".

However, Oates also paid tribute to the courage and tenacity of his enemy when he wrote: "There never were harder fighters than the Twentieth Maine men and their gallant Colonel. His skill and persistency and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac from defeat." Chamberlain in turn extolled the bravery of his Alabama foes when he later wrote: "these [the 15th Alabama] were manly men, whom we could befriend and by no means kill, if they came our way in peace and good will".

The 15th Alabama spent the remainder of the Battle of Gettysburg on the Confederate right flank, helping to secure it against Union cavalry and sharpshooters. It took no part in Pickett's Charge on July 3.[citation needed]

Out of 644 men engaged from the 15th Alabama at the Battle of Gettysburg, the regiment lost 72 men killed, 190 wounded, and 81 missing.

From Gettysburg to Appomattox

Immediate aftermath

Following the action at Gettysburg, the 15th Alabama was briefly engaged at Battle Mountain, Virginia, on July 17, reporting negligible losses. It then spent time recuperating and refitting in Virginia with the rest of Longstreet's corps, until being ordered west to bolster the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Braxton Bragg, which was operating in eastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia.

In Tennessee

During its time with Longstreet in the Army of Tennessee, the 15th Alabama participated in the following engagements:

Battle of Chickamauga on September 19-20, 1863; 19 killed and 123 wounded, out of 425 engaged.

Battle of Moccasin Point, Tennessee, on September 30, 1863; no losses given.

Battles of Browns Ferry and Lookout Valley on October 28-29, 1863; 15 killed and 40 wounded.

Battle of Campbell's Station on November 25, 1863; no losses given.

Knoxville Campaign from November 17 to December 4, 1863; 6 killed and 21 wounded.

Battle of Bean's Station on December 14, 1863; negligible losses.

Battle of Danridge on January 24, 1864; no losses given.

The 15th Alabama was the principal Confederate regiment guarding the Lookout Valley during the Union attack there; due to miscommunication between himself and three reserve regiments assigned to augment his force, Col. Oates was unable to effectively counterattack the Union force advancing up the valley from Brown's Ferry on the Tennessee River.[31] The resulting Federal victory allowed the opening of Ulysses S. Grant's famous "Cracker Line", which contributed to the breaking of the Confederate Siege of Chattanooga. Oates himself was wounded in this battle, but later recovered and continued to lead his regiment until replaced by Alexander A. Lowther in July 1864.

For its actions during the Battle of Chickamauga, the 15th was once again mentioned in dispatches, this time by Brig. Gen. Zachariah C. Deas, who wrote that the "regiment behaved with great gallantry" during the battle.

Having quarreled with Bragg during his time in Tennessee, Longstreet decided to return to Virginia with his corps (including the 15th Alabama) in the spring of 1864. Here, the 15th participated in the following engagements:

Battle of the Wilderness from May 5 to 7, 1864; 4 killed and 27 wounded, with 11 captured.

Battle of Spotsylvania Court House from May 8 to 21, 1864; 18 killed and 48 wounded, with 2 captured.

Battle of North Anna on May 24, 1864; 1 wounded.

Battle of Ashland on May 31, 1864; 1 killed.

Battle of Cold Harbor on July 1, 1864; 5 killed and 12 wounded.

Battle of Chester Station on July 17, 1864; no losses given.

Siege of Petersburg from June 18-26 of 1864, July 19 to 25, 1864, and April 2, 1865; total losses 3 killed and 2 wounded.

Battle of New Market Heights (not to be confused with the Battle of New Market) on August 14 and 15, 1864; no losses given.

Battle of Fussell's Mill on August 14, 1864; 13 killed and 90 wounded.

Battle of Ft. Gilmer on September 29, 1864; 1 wounded.

Battle of Ft. Harrison on September 30, 1864; 6 killed and 6 wounded.

Battle of Darbytown Road on October 7 and 13, 1864; 2 killed and 36 wounded.

Battle of Williamsburg Road on October 27, 1864; no losses given.

Appomattox Campaign from March 29 to April 9, 1865; no losses given.

The 15th Alabama continued to serve until the surrender of Lee's army at Appomattox Court House on April 9. It was paroled together with the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia, and its surviving members made their way back to Alabama where they resumed their lives as civilians. At the time of its surrender, the 15th had been transferred to Perry's "Florida Brigade", under the command of Col. David Lang.

The regimental commander at the time of surrender was Capt. Francis Key Schaff, formerly of Co. "A".

In 1904 and 1905, an aged William Oates and Joshua Chamberlain waged what one writer described as "one last battle" over the proposed construction of a monument on the Little Round Top to the 15th Alabama. While Chamberlain indicated that he had no quarrel whatsoever to the erection of a memorial to his old enemies, he strenuously objected to the precise spot proposed by Oates, which he insisted was farther up the hill than Oates' regiment had actually gotten during the battle. A somewhat-testy exchange of letters between the two men failed to resolve their differences, and no monument to the 15th Alabama was ever erected. Chamberlain had visited the battlefield several years after the war, and had personally directed the removal of a pile of stones placed atop Little Round Top by veterans of the 15th Alabama. At the time, as he did later in his conflict with Oates, Chamberlain stated that he had no objections to the erection of a monument to the 15th, but not atop the hill that so many of his men had died to hold. More recent efforts to create a pile of stones atop the Little Round Top have been foiled by Gettysburg park rangers.4,5

He enlisted in July 03, 1861 in Abbeville, Alabama.

Side Note:

Regimental History

THE FIFTEENTH ALABAMA INFANTRY.

The Fifteenth Alabama infantry was organized at Fort Mitchell in 1861; served in Virginia in the brigade commanded by Gen. Isaac R. Trimble; was in Stonewall Jackson's army and fought with distinction at Front Royal, May 23, 1862; Winchester, May 25th; Cross Keys, June 8th; Gaines' Mill or Cold Harbor, June 27th and 28th; Malvern Hill, July 1st, and Hazel River, August 22nd.

It fought and lost heavily at Second Manassas, August 30th, and was in the battles of Chantilly, September 1st; Sharpsburg, September 17th; Fredericksburg, December 13th; Suffolk, May, 1863; Gettysburg, July I to 3, 1863.

Ordered to join Bragg's army, the regiment fought at Chickamauga

September 19th and 20th; Brown's Ferry, October 27th; Wauhatchie, October :7th; Knoxville, November 17th to December 4th; Bean's Station, December 14th. Returning to Virginia this regiment upheld its reputation and won further distinction, as shown by its long roll of honor at Fort Harrison. It was engaged at the Wilderness, May 5-7, 1864; Spottsylvania, May 8th to 18th; Hanover Court House, May 30th; and Second Cold Harbor, June 1st to 12th.

It was also engaged before Petersburg and Richmond. At Deep Bottom, August 14th to 18th, one-third of that portion of the regiment engaged were killed.

Among its killed in battle were Capt. R. H. Hill and Lieut. W. B. Mills, at Cross Keys; Captain Weams (mortally wounded), at Gaines' Mill; Capt. P. V. Guerry and Lieut. A. McIntosh, at Cold Harbor; Capts. J. H. Allison and H. C. Brainard, at Gettysburg,and Capt. John C. Oates died of wounds received in the same battle; Capt. Frank Park was killed at Knoxville, Captain Glover at Petersburg, and Capt. B. A. Hill at Fussell's Mill.

Among the other field officers were: Cols. John F. Trentlen, Alexander Lowther, William C. Oates (who was distinguished throughout the war and has since served many years as a member of Congress and also as governor of Alabama); Col. James Cantey, afterward brigadier-general; Lieut.-Col. Isaac B. Feagin and Maj. John W. L. Daniel.

Source: Confederate Military History, vol. VIII, p. 102

Gettysburg after battle report:

Report of Col. William C. Oates, Fifteenth Alabama Infantry.

August 8, 1863.

Sir: I have the honor to report, in obedience to orders from brigade headquarters, the participation of my regiment in the battle near Gettysburg on the 2d ultimo.

My regiment occupied the center of the brigade when the line of battle was formed. During the advance, the two regiments on my right were moved by the left flank across my rear, which threw me on the extreme right of the whole line. I encountered the enemy's sharpshooters posted behind a stone fence, and sustained some loss thereby. It was here that Lieut. Col. Isaac B. Feagin, a most excellent and gallant officer, received a severe wound in the right knee, which caused him to lose his leg. Privates [A.] Kennedy, of Company B, and [William] Trimner, of Company G, were killed at this point, and Private [G. E.] Spencer, Company D, severely wounded.

After crossing the fence, I received an order from Brig.-Gen.Law to left-wheel my regiment and move in the direction of the heights upon my left, which order I failed to obey, for the reason that when I received it I was rapidly advancing up the mountain, and in my front I discovered a heavy force of the enemy. Besides this, there was great difficulty in accomplishing the maneuver at that moment, as the regiment on my left (Forty-seventh Alabama) was crowding me on the left, and running into my regiment, which had already created considerable confusion. In the event that I had obeyed the order, I should have come in contact with the regiment on my left, and also have exposed my right flank to an enfilading fire from the enemy. I therefore continued to press forward, my right passing over the top of the mountain, on the right of the line.

On reaching the foot of the mountain below, I found the enemy in heavy force, posted in rear of large rocks upon a slight elevation beyond a depression of some 300 yards in width between the base of the mountain and the open plain beyond. I engaged them, my right meeting the left of their line exactly. Here I lost several gallant officers and men.

After firing two or three rounds, I discovered that the enemy were giving way in my front. I ordered a charge, and he enemy in my front fled, but that portion of his line confronting the two companies on my left held their ground, and continued a most galling fire upon my left.

Just at this moment, I discovered the regiment on my left (Forty-seventh Alabama) retiring. I halted my regiment as its left reached a very large rock, and ordered a left-wheel of the regiment, which was executed in good order under fire, thus taking advantage of a ledge of rocks running off in a line perpendicular to the one I had just abandoned, and affording very good protection to my men. This position enabled me to keep up a constant flank and cross fire upon the enemy, which in less than five minutes caused him to change front. Receiving re-enforcements, he charged me five times, and was as often repulsed with heavy loss. Finally, I discovered that the enemy had flanked me on the right, and two regiments were moving rapidly upon my rear and not 200 yards distant, when, to save my regiment from capture or destruction, I ordered a retreat.

Having become exhausted from fatigue and the excessive heat of the day, I turned the command of the regiment over to Capt. B. A. Hill, and instructed him to take the men off the field, and reform the regiment and report to the brigade.

My loss was, as near as can now be ascertained, as follows, to wit: 17 killed upon the field, 54 wounded and brought off the field, and 90 missing, most of whom are either killed or wounded. Among the killed and wounded are 8 officers, most of whom were very gallant and efficient men.

Recapitulation.--Killed, 17; wounded, 54; missing, 90; total, 161.

I am, lieutenant, most respectfully, your obedient servant,

W. C. OATES,

Col., Comdg. Fifteenth Alabama Regt.

Lieut. B. O. Peterson,

Acting Assistant Adjutant-Gen.

Source: Official Records: Series I. Vol. 27. Part II. Reports. Serial No. 44

Battles Fought

Fought on 25 Jul 1862.

Fought on 22 Aug 1862.

Fought on 28 Aug 1862 at 2nd Manassas, VA.

Fought on 1 Jul 1863 at Gettysburg, PA.

Fought on 3 Jul 1863 at Gettysburg, PA.

Fought on 20 Sep 1863 at Chickamauga, GA.

Fought on 25 Nov 1863 at Missionary Ridge, TN.

Fought on 27 Nov 1863 at Knoxville, TN.

Fought on 6 May 1864 at Wilderness, VA.

Fought on 4 Jun 1864 at Cold Harbor, VA.

Fought on 14 Aug 1864 at Petersburg, VA.

Fought on 16 Aug 1864 at Petersburg, VA.

Fought on 17 Aug 1864 at Petersburg, VA.

Fought on 7 Oct 1864 at Darbytown Road, VA.6

He was severely wounded in the leg at the Battle of Chickamauga (September 18 to 20, 1863). He leg was amputated as a result of his wound and disabled.5 Larkin M. Bagwell married Argent Gay in 1876 at Reynolds, Dale County, Alabama. Larkin M. Bagwell married Frances G. Johnson on 20 November 1901 at Dale County, Alabama. Larkin M. Bagwell died on 29 January 1905 in Ozark, Dale County, Alabama, at age 63.3 He was buried at Old Center Methodist Church Cemetery, Newville, Henry County, Alabama.3

The 15th Regiment of Alabama Infantry was a Confederate volunteer infantry unit from the state of Alabama during the American Civil War. Recruited from six counties in the southeastern part of the state, it fought mostly with Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, though it also saw brief service with Braxton Bragg and the Army of Tennessee in late 1863 before returning to Virginia in early 1864 for the duration of the war. Out of 1958 men listed on the regimental rolls throughout the conflict, 261 are known to have fallen in battle, with sources listing an additional 416 deaths due to disease. 218 were captured (46 died), 66 deserted and 61 were transferred or discharged. By the end of the war, only 170 men remained to be paroled.

The 15th Alabama is most famous for being the regiment that confronted the 20th Maine on Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. Despite several ferocious assaults, the 15th Alabama was ultimately unable to dislodge the Union troops, and was eventually forced to retreat in the face of a desperate bayonet charge led by the 20th Maine's commander, Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain. This assault was recreated in Ronald F. Maxwell's 1993 film Gettysburg.

The 15th Alabama was organized by James Cantey, a planter originally from South Carolina, who was residing in Russell County, Alabama, at the outset of the Civil War. "Cantey's Rifles" formed at Ft. Mitchell, on the Chattahoochee River, in May 1861. Cantey's company was joined by ten other militia companies, all of which were sworn into state service by governor Andrew B. Moore on July 3, 1861, with Cantey as Regimental Commander.

One of these companies, from Henry County, was formed by William C. Oates, a lawyer and newspaperman from Abbeville. Oates, who would later command the whole regiment at Little Round Top, put together a company composed mostly of Irishmen recruited from the area, calling them "Henry Pioneers" or "Henry County Pioneers". Other observers, after seeing their colorful uniforms (bright red shirts, with Richmond grey frock coats and trousers), dubbed them "Oates' Zouaves".

According to one source, the youngest private in the 15th Alabama was only thirteen years old; the oldest, Edmond Shepherd, was seventy.

The 15th initially consisted of approximately 900 men; its companies, and their counties of origin, were:

Co. "A", known as "Cantey's Rifles", from Russell County;

Co. "B", known as the "Midway Southern Guards", from Barbour County;

Co. "C", no nickname given, from Macon County;

Co. "D", known as the "Fort Browder Roughs", from Barbour County;

Co. "E", known as the "Beauregards", from Dale County (which then included parts of present-day Geneva and Houston counties);

Co. "F", known as the "Brundidge Guards", from Pike County;

Co. "G", known as the "Henry Pioneers", from Henry County (which then included nearly all of present-day Houston County);

Co. "H", known as the "Glenville Guards", from Barbour and Dale counties;

Co. "I", no nickname given, from Pike County;

Co. "K", known as the "Eufaula City Guard", from Barbour County; and

Co. "L", no nickname given, from Pike County.

Following its formal swearing-in, the 15th Alabama was ordered to Pageland Field, Virginia, for training and drill. During their sojourn at Pageland, the regiment lost 150 men to measles. In September 1861, the 15th was transferred to Camp Toombes, Virginia, in part to escape the measles outbreak.

Companies "A" and "B" of the 15th Alabama were equipped with the M1841 Mississippi Rifle, a .54 caliber percussion rifle that had seen extensive service in the Mexican-American War and was highly regarded for its accuracy and ease of use. The other companies in the regiment were given older "George Law" smoothbore muskets, which had been converted from flintlocks to percussion rifles. Later, the regiment received British Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-muskets and Springfield Model 1861 rifled muskets. Since the 15th had initially enlisted for three years, it received its arms from the Confederate government, which refused to provide weapons to any regiment enlisting for a lesser period.

While details of the specific uniforms worn by other companies of the 15th has not been preserved, Oates' Co. "G" is recorded to have sported, in addition to their red and gray clothing, a "colorful and diverse attire of headgear". Each cap bore an "HP" insignia, which stood for "Henry Pioneers" (though some said it actually meant "Hell's Pelters"). Each soldier also wore a "secession badge", with the motto: "Liberty, Equality and Fraternity", which had been the motto of the French Revolution.

At Camp Toombs, the 15th Alabama was brigaded with the 21st Georgia Volunteer Infantry, the 21st North Carolina Infantry and the 16th Mississippi Infantry regiments in Trimble's Brigade of Ewell's Division, part of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. After that force moved over toward Yorktown, the 15th was transferred to Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson's division, where it participated in his Valley Campaign. During this time, the 15th participated in the following engagements:

Battle of Front Royal on May 23, 1862; negligible losses.

First Battle of Winchester on May 25, 1862; negligible losses.

Battle of Cross Keys on June 8, 1862; 9 killed and 33 wounded, out of 426 engaged.

Following the Battle of Cross Keys, the 15th was mentioned in dispatches by its division commander, Maj. Gen. Ewell, who stated that "the regiment made a gallant resistance, enabling me to take position at leisure". Its brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Trimble, also singled out the regiment for honors during this engagement: "to Colonel Cantey for his skillful retreat from picket, and prompt flank maneuver, I think special praise is due". During this particular engagement, soldiers of the 15th Alabama had the unusual opportunity of participating in every major phase of a single battle, starting with the opening skirmish at Union Church on the forward left flank, followed by withdrawing beneath the artillery duel in the center, and then finally participating in Trimble's ambush of the 8th New York and subsequent counterattack on the Confederate right flank, which brought the battle to its conclusion.

Seven Days Battles

Following the victorious conclusion of Jackson's Valley Campaign, the 15th participated in Jackson's attack on Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's flank during the Seven Days Battles. During this time, the 15th fought in the following sorties:

Second Battle of Manassas battlefield

Battle of Gaines' Mill on June 27-28, 1862; 34 killed and 110 wounded, out of 412 engaged.

Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862; negligible losses.

Northern Virginia Campaign

Following McClellan's retreat from Richmond, the 15th was engaged in the Northern Virginia Campaign, where it participated in the following battles:

Battle of Warrenton Springs Ford on August 12, 1862; losses not given.

Battle of Hazel River, Virginia, on August 22, 1862; losses not given.

Battle of Kettle Run (called "Manassas Junction" in regimental records) on August 30, 1862; 6 killed and 22 wounded.

Second Battle of Manassas, on August 30, 1862; 21 killed and 91 wounded, out of 440 engaged.

Battle of Chantilly, on September 1, 1862; 4 killed and 14 wounded.

Battle of Antietam by Kurz and Allison

Maryland Campaign

Next up was Lee's Maryland Campaign, where the 15th Alabama saw action at:

Battle of Harper's Ferry from September 12-15, 1862; negligible losses.

Battle of Antietam (called "Sharpsburg" in regimental records) on September 17, 1862; 9 killed and 75 wounded, out of 300 engaged.

Battle of Shepherdstown on September 19, 1862; losses not given.

After Antietam, acting brigade commander Col. James A. Walker cited Cpt. Isaac B. Feagin, acting regimental commander, for outstanding performance while extolling the regiment as a whole: "Captain Feagin, commanding the Fifteenth Alabama regiment, behaved with a gallantry consistent with his high reputation for courage and that of the regiment he commanded".

Fredericksburg and Suffolk; reassignment

Following the Confederate defeat at Antietam, the 15th Alabama participated with Jackson's corps at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 15, 1862. Total casualties there were 1 killed and 34 wounded. The regiment was then reassigned in May 1863 to General James Longstreet's corps, which was then participating in the Siege of Suffolk, Virginia. Here it formed part of the newly created "Alabama Brigade" under Evander Law in General Hood's division, The 15th and lost 4 killed and 18 wounded at Suffolk.

The Great Snowball Fight

On January 29, 1863, the 15th Alabama participated with several other regiments of the Army of Northern Virginia in what became known as "The Great Snowball Fight of 1863". Over 9000 Confederate soldiers engaged in a spontaneous, day-long free-for-all using snowballs and rocks, in which only two soldiers were seriously injured (neither from the 15th).

Oates takes command

Along with its change in Divisional assignment, the 15th Alabama received a new regimental commander: Lt. Col. William C. Oates, who had originally organized Co. "G" when the regiment first formed in 1861. Oates had lived a drifter's existence in Texas during his early adulthood, participating in numerous street brawls and spending time as a gambler. However, by 1861 he had returned to Alabama, finished his schooling, studied law, and set up a successful practice in Henry County that also included ownership of a weekly newspaper in his hometown. Opposed to Abraham Lincoln's election, Oates cautioned against precipitate secession; however, once Alabama decided to leave the Union, he threw himself wholeheartedly into the Southern cause, raising a company of volunteers that became Co. "G" of the 15th Alabama. After Cantey's promotion and transfer to a new position, Oates assumed command of the regiment as a whole. In later years, Oates would serve as Governor of Alabama, and would also command three U.S. Brigades (none of which saw combat) during the Spanish-American War.

While some of his men thought Oates to be too aggressive for his own good and theirs, most admired his courage and affirmed that he was always to be found at the front of his men, in the thick of combat, and that he never asked them to go anywhere that he was not willing to go himself. A political rival, Alexander Lowther, would replace Oates as regimental commander in July 1864 after allegedly engineering Oates' removal from command. It was Oates, however, who led the 15th Alabama into its most noted engagement of the war, at Little Round Top on July 2, 1863, during the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Action at Gettysburg

Main articles: Battle of Gettysburg, Second Day and Little Round Top

Little Round Top

During the Battle of Gettysburg, the 15th Alabama and the rest of Law's Brigade formed part of Maj. Gen. John B. Hood's division, which was a part of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's corps. Arriving on the field late in the evening on July 1, the 15th played no appreciable role in the contest's first day. This changed on the 2nd, as Gen. Robert E. Lee had ordered Longstreet to launch a surprise attack with two of his divisions against the Federal left flank and their positions atop Cemetery Hill. During the course of this engagement, which was launched late in the afternoon of July 2, the 15th Alabama found itself advancing over rough terrain on the eastern side of the Emmitsburg Road, which combined with fire from the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters at nearby Slyder's Farm to compel Law's brigade (including the 15th Alabama) to detour around the Devil's Den and over the Big Round Top toward Little Round Top. During this time, the 15th was under constant fire from Federal sharpshooters, and the regiment became temporarily separated from the rest of the Alabama brigade as it made its way over Big Round Top.

Little Round Top, which dominated the Union position on Cemetery Ridge, was initially unoccupied by Union troops. Union commander Maj. Gen. George Meade's chief engineer, Brig. Gen Gouverneur K. Warren, had climbed the hill on his superior's orders to assess the situation there; he noticed the glint of Confederate bayonets to the hill's southwest, and realized that a Southern attack was imminent. Warren's frantic cry for reinforcements to occupy the hill was answered by Col. Strong Vincent, commanding the Third Brigade of the First Division of the Union V Corps. Vincent rapidly moved the four regiments of his brigade onto the hill, only ten minutes ahead of the approaching Confederates. Under heavy fire from Southern batteries, Vincent arranged his four regiments atop the hill with the 16th Michigan to the northwest, then proceeding counterclockwise with the 44th New York, the 83rd Pennsylvania, and finally, at the end of the line on the southern slope, the 20th Maine. With only minutes to spare, Vincent told his regiments to take cover and await the inevitable Confederate assault; he specifically ordered Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain, commanding the 20th Maine (at the extreme end of the Union line), to hold his position to the last man, at all costs. Were Chamberlain's regiment to be forced to retreat, the other regiments on the hill would be compelled to follow suit, and the entire left flank of Meade's army would be in serious jeopardy, possibly leading them to retreat and giving the Confederates their desperately needed victory at Gettysburg.

The 15th Alabama attacks

In their attack on Little Round Top, the 15th Alabama would be joined by the 4th and 47th Alabama Infantry, and also by the 4th and 5th Texas Infantry regiments. All of these units were thoroughly exhausted at the time of the assault, having marched in the July heat for over 20 miles (37 kilometers) prior to the actual attack. Furthermore, the canteens of the Southerners were empty, and Law's command to advance did not give them time to refill them. Approaching the Union line on the crest of the hill, Law's men were thrown back by the first Union volley and withdrew briefly to regroup. The 15th Alabama repositioned itself further to the right, attempting to find the Union left flank which, unbeknownst to it, was held by Chamberlain's 20th Maine.

Chamberlain, meanwhile, had detached Company "B" of his regiment and elements of the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters, ordering them to take a concealed position behind a stone wall 150 yards to his east, hoping to guard against a Confederate envelopment.

Seeing the 15th Alabama shifting around his flank, Chamberlain ordered the remainder of his 385 men to form a single-file line. The 15th Alabama charged the Maine troops, only to be repulsed by furious rifle fire. Chamberlain next ordered the southernmost half of his line to "refuse the line", meaning that they formed a new line at an angle to the original force, to meet the 15th Alabama's flanking maneuver. Though it endured incredible losses, the 20th Maine managed to hold through five more charges by the 15th over a ninety-minute period. Col. Oates, commanding the regiment, described the action in his memoirs, forty years later:

"Vincent's brigade, consisting of the Sixteenth Michigan on the right, Forty-fourth New York, Eighty-third Pennsylvania, and Twentieth Maine regiments, reached this position ten minutes before my arrival, and they piled a few rocks from boulder to boulder, making the zigzag line more complete, and were concealed behind it ready to receive us. From behind this ledge, unexpectedly to us, because concealed, they poured into us the most destructive fire I ever saw. Our line halted, but did not break. The enemy was formed in line as named from their right to left. ... As men fell their comrades closed the gap, returning the fire most spiritedly. I could see through the smoke men of the Twentieth Maine in front of my right wing running from tree to tree back westward toward the main body, and I advanced my right, swinging it around, overlapping and turning their left. I ordered my regiment to change direction to the left, swing around, and drive the Federals from the ledge of rocks, for the purpose of enfilading their line ... gain the enemy's rear, and drive him from the hill. My men obeyed and advanced about half way to the enemy's position, but the fire was so destructive that my line wavered like a man trying to walk against a strong wind, and then slowly, doggedly, gave back a little; then with no one upon the left or right of me, my regiment exposed, while the enemy was still under cover, to stand there and die was sheer folly; either to retreat or advance became a necessity. ... Captain [Henry C.] Brainard, one of the bravest and best officers in the regiment, in leading his company forward, fell, exclaiming, 'O God! that I could see my mother,' and instantly expired. Lieutenant John A. Oates, my dear brother, succeeded to the command of the company, but was pierced through by a number of bullets, and fell mortally wounded. Lieutenant [Barnett H.] Cody fell mortally wounded, Captain [William C.] Bethune and several other officers were seriously wounded, while the carnage in the ranks was appalling. I again ordered the advance, knowing the officers and men of that gallant old regiment, I felt sure that they would follow their commanding officer anywhere in the line of duty. I passed through the line waving my sword, shouting, 'Forward, men, to the ledge!' and promptly followed by the command in splendid style. We drove the Federals from their strong defensive position; five times they rallied and charged us, twice coming so near that some of my men had to use the bayonet, but in vain was their effort. It was our time now to deal death and destruction to a gallant foe, and the account was speedily settled. I led this charge and sprang upon the ledge of rock, using my pistol within musket length, when the rush of my men drove the Maine men from the ledge. ... About forty steps up the slope there is a large boulder about midway the Spur. The Maine regiment charged my line, coming right up in a hand-to-hand encounter. My regimental colors were just a step or two to the right of that boulder, and I was within ten feet. A Maine man reached to grasp the staff of the colors when Ensign [John G.] Archibald stepped back and Sergeant Pat O'Connor stove his bayonet through the head of the Yankee, who fell dead."

Battle of Little Round Top, final assault, showing the 15th Alabama's assault against the 20th Maine

Chamberlain's desperate charge

Out of ammunition, and facing what he was sure would be yet another determined assault by the Alabamians, Col. Chamberlain decided upon a most unorthodox response: ordering his men to fix bayonets, he led what was left of his outfit in a pell-mell charge down the hill, executing a combined frontal assault and flanking maneuver that caught the 15th Alabama completely by surprise. Unbeknownst to Chamberlain, Oates had already decided to retreat, realizing that his ammunition was running low, and worried about a possible Union attack on his own flank or rear. His younger brother lay dying on the field, and the blood from his regiment's dead and wounded "was standing in puddles on some of the rocks". Hardly had Oates ordered the withdrawal than Chamberlain began his charge, which combined with fire from "B" company and the hidden sharpshooters to cause the 15th to rush madly down the hill to escape. Oates later admitted that "we ran like a herd of wild cattle" during the retreat, which took those surviving members of the 15th (including Oates) who weren't captured by Chamberlain's men up the slopes of Big Round Top and toward Confederate lines.

In later years, Oates would assert that the 15th Alabama's assault had failed because no other Confederate regiment appeared in support of his unit during the attack. He insisted that if but one other regiment had joined his attack on the far left of the Union army, they would have swept the 20th Maine from the hill and turned the Union flank, "which would have forced Meade's whole left wing to retire".

However, Oates also paid tribute to the courage and tenacity of his enemy when he wrote: "There never were harder fighters than the Twentieth Maine men and their gallant Colonel. His skill and persistency and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac from defeat." Chamberlain in turn extolled the bravery of his Alabama foes when he later wrote: "these [the 15th Alabama] were manly men, whom we could befriend and by no means kill, if they came our way in peace and good will".

The 15th Alabama spent the remainder of the Battle of Gettysburg on the Confederate right flank, helping to secure it against Union cavalry and sharpshooters. It took no part in Pickett's Charge on July 3.[citation needed]

Out of 644 men engaged from the 15th Alabama at the Battle of Gettysburg, the regiment lost 72 men killed, 190 wounded, and 81 missing.

From Gettysburg to Appomattox

Immediate aftermath

Following the action at Gettysburg, the 15th Alabama was briefly engaged at Battle Mountain, Virginia, on July 17, reporting negligible losses. It then spent time recuperating and refitting in Virginia with the rest of Longstreet's corps, until being ordered west to bolster the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Braxton Bragg, which was operating in eastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia.

In Tennessee

During its time with Longstreet in the Army of Tennessee, the 15th Alabama participated in the following engagements:

Battle of Chickamauga on September 19-20, 1863; 19 killed and 123 wounded, out of 425 engaged.

Battle of Moccasin Point, Tennessee, on September 30, 1863; no losses given.

Battles of Browns Ferry and Lookout Valley on October 28-29, 1863; 15 killed and 40 wounded.

Battle of Campbell's Station on November 25, 1863; no losses given.

Knoxville Campaign from November 17 to December 4, 1863; 6 killed and 21 wounded.

Battle of Bean's Station on December 14, 1863; negligible losses.

Battle of Danridge on January 24, 1864; no losses given.

The 15th Alabama was the principal Confederate regiment guarding the Lookout Valley during the Union attack there; due to miscommunication between himself and three reserve regiments assigned to augment his force, Col. Oates was unable to effectively counterattack the Union force advancing up the valley from Brown's Ferry on the Tennessee River.[31] The resulting Federal victory allowed the opening of Ulysses S. Grant's famous "Cracker Line", which contributed to the breaking of the Confederate Siege of Chattanooga. Oates himself was wounded in this battle, but later recovered and continued to lead his regiment until replaced by Alexander A. Lowther in July 1864.

For its actions during the Battle of Chickamauga, the 15th was once again mentioned in dispatches, this time by Brig. Gen. Zachariah C. Deas, who wrote that the "regiment behaved with great gallantry" during the battle.

Having quarreled with Bragg during his time in Tennessee, Longstreet decided to return to Virginia with his corps (including the 15th Alabama) in the spring of 1864. Here, the 15th participated in the following engagements:

Battle of the Wilderness from May 5 to 7, 1864; 4 killed and 27 wounded, with 11 captured.

Battle of Spotsylvania Court House from May 8 to 21, 1864; 18 killed and 48 wounded, with 2 captured.

Battle of North Anna on May 24, 1864; 1 wounded.

Battle of Ashland on May 31, 1864; 1 killed.

Battle of Cold Harbor on July 1, 1864; 5 killed and 12 wounded.

Battle of Chester Station on July 17, 1864; no losses given.

Siege of Petersburg from June 18-26 of 1864, July 19 to 25, 1864, and April 2, 1865; total losses 3 killed and 2 wounded.

Battle of New Market Heights (not to be confused with the Battle of New Market) on August 14 and 15, 1864; no losses given.

Battle of Fussell's Mill on August 14, 1864; 13 killed and 90 wounded.

Battle of Ft. Gilmer on September 29, 1864; 1 wounded.

Battle of Ft. Harrison on September 30, 1864; 6 killed and 6 wounded.

Battle of Darbytown Road on October 7 and 13, 1864; 2 killed and 36 wounded.

Battle of Williamsburg Road on October 27, 1864; no losses given.

Appomattox Campaign from March 29 to April 9, 1865; no losses given.

The 15th Alabama continued to serve until the surrender of Lee's army at Appomattox Court House on April 9. It was paroled together with the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia, and its surviving members made their way back to Alabama where they resumed their lives as civilians. At the time of its surrender, the 15th had been transferred to Perry's "Florida Brigade", under the command of Col. David Lang.

The regimental commander at the time of surrender was Capt. Francis Key Schaff, formerly of Co. "A".

In 1904 and 1905, an aged William Oates and Joshua Chamberlain waged what one writer described as "one last battle" over the proposed construction of a monument on the Little Round Top to the 15th Alabama. While Chamberlain indicated that he had no quarrel whatsoever to the erection of a memorial to his old enemies, he strenuously objected to the precise spot proposed by Oates, which he insisted was farther up the hill than Oates' regiment had actually gotten during the battle. A somewhat-testy exchange of letters between the two men failed to resolve their differences, and no monument to the 15th Alabama was ever erected. Chamberlain had visited the battlefield several years after the war, and had personally directed the removal of a pile of stones placed atop Little Round Top by veterans of the 15th Alabama. At the time, as he did later in his conflict with Oates, Chamberlain stated that he had no objections to the erection of a monument to the 15th, but not atop the hill that so many of his men had died to hold. More recent efforts to create a pile of stones atop the Little Round Top have been foiled by Gettysburg park rangers.4,5

He enlisted in July 03, 1861 in Abbeville, Alabama.

Side Note:

Regimental History

THE FIFTEENTH ALABAMA INFANTRY.

The Fifteenth Alabama infantry was organized at Fort Mitchell in 1861; served in Virginia in the brigade commanded by Gen. Isaac R. Trimble; was in Stonewall Jackson's army and fought with distinction at Front Royal, May 23, 1862; Winchester, May 25th; Cross Keys, June 8th; Gaines' Mill or Cold Harbor, June 27th and 28th; Malvern Hill, July 1st, and Hazel River, August 22nd.

It fought and lost heavily at Second Manassas, August 30th, and was in the battles of Chantilly, September 1st; Sharpsburg, September 17th; Fredericksburg, December 13th; Suffolk, May, 1863; Gettysburg, July I to 3, 1863.

Ordered to join Bragg's army, the regiment fought at Chickamauga

September 19th and 20th; Brown's Ferry, October 27th; Wauhatchie, October :7th; Knoxville, November 17th to December 4th; Bean's Station, December 14th. Returning to Virginia this regiment upheld its reputation and won further distinction, as shown by its long roll of honor at Fort Harrison. It was engaged at the Wilderness, May 5-7, 1864; Spottsylvania, May 8th to 18th; Hanover Court House, May 30th; and Second Cold Harbor, June 1st to 12th.

It was also engaged before Petersburg and Richmond. At Deep Bottom, August 14th to 18th, one-third of that portion of the regiment engaged were killed.

Among its killed in battle were Capt. R. H. Hill and Lieut. W. B. Mills, at Cross Keys; Captain Weams (mortally wounded), at Gaines' Mill; Capt. P. V. Guerry and Lieut. A. McIntosh, at Cold Harbor; Capts. J. H. Allison and H. C. Brainard, at Gettysburg,and Capt. John C. Oates died of wounds received in the same battle; Capt. Frank Park was killed at Knoxville, Captain Glover at Petersburg, and Capt. B. A. Hill at Fussell's Mill.

Among the other field officers were: Cols. John F. Trentlen, Alexander Lowther, William C. Oates (who was distinguished throughout the war and has since served many years as a member of Congress and also as governor of Alabama); Col. James Cantey, afterward brigadier-general; Lieut.-Col. Isaac B. Feagin and Maj. John W. L. Daniel.

Source: Confederate Military History, vol. VIII, p. 102

Gettysburg after battle report:

Report of Col. William C. Oates, Fifteenth Alabama Infantry.

August 8, 1863.

Sir: I have the honor to report, in obedience to orders from brigade headquarters, the participation of my regiment in the battle near Gettysburg on the 2d ultimo.

My regiment occupied the center of the brigade when the line of battle was formed. During the advance, the two regiments on my right were moved by the left flank across my rear, which threw me on the extreme right of the whole line. I encountered the enemy's sharpshooters posted behind a stone fence, and sustained some loss thereby. It was here that Lieut. Col. Isaac B. Feagin, a most excellent and gallant officer, received a severe wound in the right knee, which caused him to lose his leg. Privates [A.] Kennedy, of Company B, and [William] Trimner, of Company G, were killed at this point, and Private [G. E.] Spencer, Company D, severely wounded.

After crossing the fence, I received an order from Brig.-Gen.Law to left-wheel my regiment and move in the direction of the heights upon my left, which order I failed to obey, for the reason that when I received it I was rapidly advancing up the mountain, and in my front I discovered a heavy force of the enemy. Besides this, there was great difficulty in accomplishing the maneuver at that moment, as the regiment on my left (Forty-seventh Alabama) was crowding me on the left, and running into my regiment, which had already created considerable confusion. In the event that I had obeyed the order, I should have come in contact with the regiment on my left, and also have exposed my right flank to an enfilading fire from the enemy. I therefore continued to press forward, my right passing over the top of the mountain, on the right of the line.

On reaching the foot of the mountain below, I found the enemy in heavy force, posted in rear of large rocks upon a slight elevation beyond a depression of some 300 yards in width between the base of the mountain and the open plain beyond. I engaged them, my right meeting the left of their line exactly. Here I lost several gallant officers and men.

After firing two or three rounds, I discovered that the enemy were giving way in my front. I ordered a charge, and he enemy in my front fled, but that portion of his line confronting the two companies on my left held their ground, and continued a most galling fire upon my left.

Just at this moment, I discovered the regiment on my left (Forty-seventh Alabama) retiring. I halted my regiment as its left reached a very large rock, and ordered a left-wheel of the regiment, which was executed in good order under fire, thus taking advantage of a ledge of rocks running off in a line perpendicular to the one I had just abandoned, and affording very good protection to my men. This position enabled me to keep up a constant flank and cross fire upon the enemy, which in less than five minutes caused him to change front. Receiving re-enforcements, he charged me five times, and was as often repulsed with heavy loss. Finally, I discovered that the enemy had flanked me on the right, and two regiments were moving rapidly upon my rear and not 200 yards distant, when, to save my regiment from capture or destruction, I ordered a retreat.

Having become exhausted from fatigue and the excessive heat of the day, I turned the command of the regiment over to Capt. B. A. Hill, and instructed him to take the men off the field, and reform the regiment and report to the brigade.

My loss was, as near as can now be ascertained, as follows, to wit: 17 killed upon the field, 54 wounded and brought off the field, and 90 missing, most of whom are either killed or wounded. Among the killed and wounded are 8 officers, most of whom were very gallant and efficient men.

Recapitulation.--Killed, 17; wounded, 54; missing, 90; total, 161.

I am, lieutenant, most respectfully, your obedient servant,

W. C. OATES,

Col., Comdg. Fifteenth Alabama Regt.

Lieut. B. O. Peterson,

Acting Assistant Adjutant-Gen.

Source: Official Records: Series I. Vol. 27. Part II. Reports. Serial No. 44

Battles Fought

Fought on 25 Jul 1862.

Fought on 22 Aug 1862.

Fought on 28 Aug 1862 at 2nd Manassas, VA.

Fought on 1 Jul 1863 at Gettysburg, PA.

Fought on 3 Jul 1863 at Gettysburg, PA.

Fought on 20 Sep 1863 at Chickamauga, GA.

Fought on 25 Nov 1863 at Missionary Ridge, TN.

Fought on 27 Nov 1863 at Knoxville, TN.

Fought on 6 May 1864 at Wilderness, VA.

Fought on 4 Jun 1864 at Cold Harbor, VA.

Fought on 14 Aug 1864 at Petersburg, VA.

Fought on 16 Aug 1864 at Petersburg, VA.

Fought on 17 Aug 1864 at Petersburg, VA.

Fought on 7 Oct 1864 at Darbytown Road, VA.6

He was severely wounded in the leg at the Battle of Chickamauga (September 18 to 20, 1863). He leg was amputated as a result of his wound and disabled.5 Larkin M. Bagwell married Argent Gay in 1876 at Reynolds, Dale County, Alabama. Larkin M. Bagwell married Frances G. Johnson on 20 November 1901 at Dale County, Alabama. Larkin M. Bagwell died on 29 January 1905 in Ozark, Dale County, Alabama, at age 63.3 He was buried at Old Center Methodist Church Cemetery, Newville, Henry County, Alabama.3